Curatorial:

During the end of March 2012, Indonesians from various backgrounds were voicing outrage against the Indonesian Government’s plan to cut subsidies on the type of fuel used by most of the population, which would directly result in fuel price hike. Hundreds of demonstrations and rallies took place in many Indonesian major cities.

Days before 1 April 2012, the date when the Government’s decision is due, the demonstrations escalated in intensity, which culminated in clashes between police and protesters. The situation grew alarming nationwide as conflicts between people and the Government were in the rise. Finally, after an intense plenary session, the House rejected the fuel price hike proposal. Shortly afterwards, the issue of fuel subsididies removal gradually went out of public attention. The general public were pleased and soothed.

Nevertheless, isn’t it the truth that our dependence—and the rest of the world’s dependence—on unrenewable fossil fuel has grown to such a large extent? Isn’t it the truth that fuel prices will continually increase as supply grows scarce? Also, how long can the Government keep subsidizing fuel with its ever-increasing price? At the moment, with fuel subsidies in place, the important, urgent matters of fuel availability and fuel dependence are gone from public discussions; not deserving of public attention, let alone thoughts.

Amidst such circumstances, the House of Natural Fiber (HONF, Yogyakarta, Indonesia) have been cooking up ideas and experiments to discover alternative ways of obtaining alternative energy sources, which comprise the substance and the socio-economic-political context of the MICRONATION/MACRO-NATION project development.

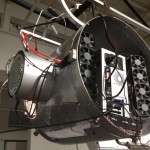

HONF’s presentation at Langgeng Art Foundation (LAF) is their starting point to introduce these ideas as well as the technical-practical implementation possibilities. The presentation—as a sustainable design prototype—consists of 3 core components: a) Installation of a fermentation/distillation machine to process hay (raw material) into ethanol (alternative energy to substitute fossil fuel); b) Satellite data grabber: to obtain data related to agricultural production (weather, climate, seasons); c) Super-Computer: to process data (weather, seasons as well as ethanol production capacity), which is also capable of predicting when Indonesia can reach energy and food independence if this MICRONATION/MACRONATION sustainable project design were to be implemented as a public strategy and policy to achieve the condition of energy and food independence in Indonesia.[1]

This presentation is a good opportunity for us to reassess basic performative premises of various practices combining science, technology and arts. HONF’s project—as with their previous projects—actually blurs the boundaries that have thus far been setting apart science, technology and arts. They combine all three, which to us brings home the question: where is the boundary between aesthetic experience and function? What possibilities could the relationship among science, technology and arts bring when confronted to actual problems in today’s communities?

Compared to various other fine arts practices involving elements of social activism which have hitherto been tested and conducted by a number of artists in Indonesia, HONF’s current project actually proposes something new and different. They no longer practice the “taking to the streets” or “teaching/utilizing arts to raise mass awareness” kinds of activism, nor do they practice arts that involve local environmental/community issues[2]. Instead they view social-political issues by assessing various strategic areas, which are not solely based on the “people versus corporate” or “people versus the State” axes.

By widening our acceptance of various dimensions of relationship which exist between the artists and the public today, we can see that HONF still employ ‘aesthetics’ in their work, although their chosen strategy of visualization naturally no longer focuses on the ‘fine arts’ conventions. For instance, data processing and presentation in their work—be it related to nature, environment or various calculations—will be shown in various forms of visualization. But this time we need to take it as visualization that may not necessarily always serve as representation (art).

Faced with ecological issues, HONF choose to activate their creativity to render such ecological issues more open and accessible by the public (creative ecology). Data which are unfamiliar—or perhaps even concealed and made secret from the general public’s knowledge—are presented in an easy-to-undertand visualization. In other words, data pertaining to public interests and public life are returned to the public (hacktivism, open-source, democratization of information dan knowledge).

Furthermore, the use of science, technology and arts in HONF’s projects should no longer be viewed through a conventional formalistic aesthetic perspective. If we can accept that this project is a design which involves a number of systems (physics, biology, mechanics, digital data-processing, and so on), what HONF have been doing is equal to the system aesthetics once proposed by Haans Haacke, a German-born artist who used to focus on issues of environmental system and social system in his works.

That way, MICRONATION/MACRONATION is a practice which may possibly bring various new elements into the practices of fine arts that have been taking place in Indonesia. Through HONF’s works so far, we are in fact presented with the opportunity to re-formulate basic relationships which can exist between the art(ists) and the public. Is this not a truly relevant issue, considering how the faster, more complex public (social, economic, politic, cultural and global) reality keeps on changing? — HONF | Enin Supriyanto | April 2012.

————-

Footnotes:

[1] At the same time, the prototype of this design is being tested through the MICRONATION/MACRONATION project simulation land in several agricultural fields and villages around Cangkringan, Merapi, Yogyakarta, in cooperation with local residents.

[2] Compare with the environment-related fine art activities and activism in Indonesia in the past.